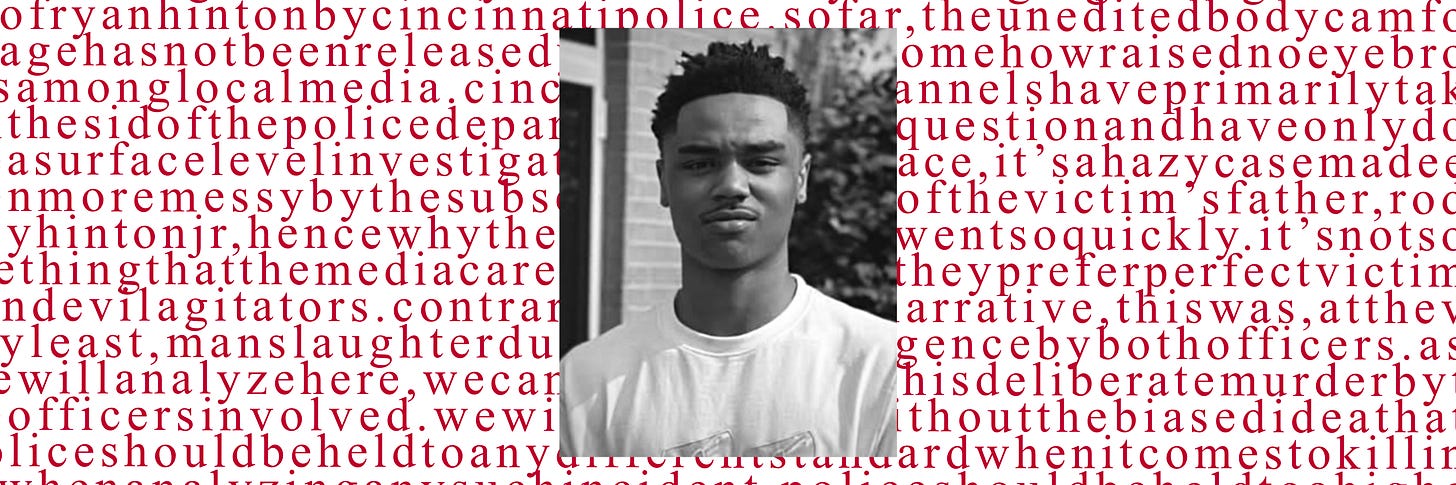

Analyzing the Murder of Ryan Hinton

Part I: Yet another instance of systematic police murder.

The coverage of this story has been sorely lacking regarding the murder of Ryan Hinton by Cincinnati police. So far, the unedited bodycam footage has not been released yet, which has somehow raised no eyebrows among local media. Cincinnati news channels have primarily taken the side of the police department without question and have only done a surface-level investigation.

On the it’s face, it’s a hazy case made even more messy by the subsequent actions of the victim’s father, Rodney Hinton Jr, hence why the story came and went so quickly. It’s not something that the media cares to scrutinize; they prefer perfect victims and evil agitators.

Contrary to the police narrative, this was, at the very least, manslaughter due to gross negligence by both officers. As we will analyze here, we can certainly call this intentional murder by the officers involved. We will look at this without the biased idea that police should be held to any different standard when it comes to killing. When analyzing any such incident, police should be held to a higher standard, not a lower standard, where they are afforded qualified immunity and infinite plausible deniability.

On May 1st, 2025, the Cincinnati Police Department tracked a vehicle stolen from northern Kentucky the previous day. Undercover officers found the Kia SUV parked in an apartment complex at 2500 Warsaw Avenue. After spotting the suspects in the car, they moved out and proceeded to initiate a confrontation using marked police vehicles. Upon seeing the police pull in, all four boys fled the car, and the two officers tried to chase them. Three got away, but one of the boys, Ryan Hinton, seemed to fall briefly, and the first officer caught up. After getting up and running between two dumpsters, the first officer was waiting on the other side, shooting him five times in the side and back, killing him.

Many problems with this case stem from the details that are not being shown and the questions that are not being asked. No additional footage was provided, except for the roughly 10 seconds of each officer’s body camera footage. The Cincinnati Police Department claims that more information will be released after the investigation, and the officer’s name will not be released due to Marsy’s Law.

This is a common tactic by Police Departments to dissipate anger over a police involved shooting: only give enough information to create a forgiving narrative, people forget over time, so when the case is dealt with and everything comes out, there’s far less outrage. This has happened multiple times before, where departments have withheld the extended video, which ultimately reveals them saying disgusting or incriminating things. Since departments have the sole authority over recordings and are given the benefit of the doubt by default in court, they can manipulate public perception at their discretion. States and municipalities have different laws regarding the recording, storage, and release of footage. Some cities, like Chicago, have more robust independent oversight along with laws to improve transparency. However, the majority of cities and towns do not adhere to these standards. Even if cities do have certain transparency laws, departments often find ways to delay, ignore, push the limits, side-step, or fight against them.

⚠️ Trigger Warning: Graphic footage

The department hangs their defense on the excuse that even though Hinton was running away, he was still a threat since he allegedly had a gun. It should go without saying that suspects of crimes under almost all circumstances should not be shot and killed for running away, something that happens far too frequently. In 2022, a research group found that an astonishing 1 in 3 suspects that are fatally shot by police were fleeing. A Supreme Court case called Tennessee v. Garner covered this forty years ago, which only limited the use of lethal force on fleeing suspects to when the officer feels threatened or perceives the suspect to be armed. The arbitrary meaning of ‘threatened’ and ‘perceived’ is precisely what protects police from any repercussions of shooting unarmed and non-threatening people. This then informally embedded itself into police culture as the law used against police concerns their subjective experience, which is already biased by judicial deference.

A cop knows that their word is worth more than an average citizen’s; that’s why you’ll always lose a traffic ticket when it’s the cop’s word against yours. You see this phenomenon when cops accuse or insistently ask people if they’re intoxicated, they gaslight and if people respond with irritation, they take it as admission. This allows them to absolve themselves of just about anything in court. This manufactured immunity enables them to abuse their power in various ways. If someone isn’t intimidated by you, say you smell alcohol on their breath or that they’re slurring their words. If someone knows their rights at a traffic stop and demands reasonable suspicion, say something subjective like you thought you saw their seatbelt off, or you smelled weed. This abuse is even more effective when cops deal with people who are on the autism spectrum, neurodiverse, or are afraid of police.

A cop also knows that when it comes to stopping a suspect, shouting “Gun!” before killing them is, in many cases, enough to clear them of wrongdoing in the eyes of the court. You notice this in body camera footage when cops fake being the victim to create the pretense that they felt danger. After all, in court, when a cop’s word is worth more, sometimes all it takes is explaining that they felt in danger. Sometimes, this may earnestly be the case as toxic police norms, especially in cities, train cops to be constantly on edge, ready to react to threats at every second. In a broader sense, it’s used as a tool to protect them from whatever bullying or abuse they may inflict.

The claim that Hinton had a gun based on the body camera alone is simply inconclusive. In both segments of the encounter, there’s no clear frame with a gun.

When Hinton fell, the footage does not clearly show a gun; he appears to push off the ground to get back up. There is a single frame that the department cherry-picked, where one could vaguely argue that a gun seems to be on the ground. In the frames before and after the one the department used, there doesn’t appear to be any object standing out against the concrete pavement.

Conveniently, the department did not release dash cam footage from the other cars at the scene or any other angle that may have shown a better view of Hinton falling. That would be able to prove definitively whether Hinton picked up the gun, if the gun stayed on the pavement, or that no gun hit the ground in the first place.

When Hinton ran out between the dumpsters, he was facing perpendicular to the officer and maintained his head in the same direction, facing toward the trees. Going frame by frame, there isn’t a single moment where Hinton even makes eye contact with the officer; he’s solely focused on getting away. The way the department describes it, Hinton, if he intended to aim at the officer, he would be shooting across his body while running full speed, shooting at a target he’s not looking at. It’s plainly ridiculous. Additionally, none of the frames show anything that resembles a gun. The blurry brown spot on the frame, which the department cited as the gun, looks much more like his hand.

This isn’t to completely discount the cop’s perspective entirely, humans can see things that aren’t actually there or even trick themselves into believing they saw something they didn’t. However, we shouldn’t base our analysis on the word of the person who has the most significant stake in saying they saw a weapon.

We see here how the two cops manufacture each other’s plausible deniability. As the lead officer (Officer 1) passes the black SUV, he gets a visual of Hinton while at the same moment, the cop lagging behind (Officer 2) begins to yell:

“He’s got a gun! He’s got a gun! On your right! On your right!”

The timestamps of both POVs are lined up so that when he starts to yell, we can see he has no visual of Hinton, not even a glimpse. How would he know that Hinton had a gun if the only time the department cites that Hinton is seen with one is in the view of Officer 1? He didn’t.

There is certainly a chance that Officer 2 saw a gun in the moment prior, but that footage hasn’t been released. It makes you wonder why such a short clip was the only evidence provided.

We also see that Officer 1 quickly says “Gun!” between the time he unholsters and when he shoots the first shot.

In court, a defense attorney can now more easily argue that because they yelled this, it indicated they perceived a gun, thus absolving them, even if one officer had no way of knowing this, and the other likely didn’t see one at all. The problem is that cops can reflexively say ‘gun’ in any stressful situation to protect themselves legally, but that ends up putting others in a dangerous situation where their death is pre-justified.

Another small detail that the department falsified is the claim that the officers were chasing other suspects. That may have been the officer’s initial objective, but according to the body cam, there are no other suspects in the vicinity.

A strange detail worth mentioning is the decision-making by Officer 1 (even though it’s functionally useless in our current police and justice system). Officer 2 is able to yell out 14 words in the approximately 6 seconds between the time Officer 1 sees Hinton on the ground and when he meets him on the other side of the dumpsters. If Officer 1 did indeed believe that the suspect had a deadly weapon, wouldn’t common sense say to be more cautious? Officer 1 watches Hinton (whom he thinks is armed) get up and start running toward the dumpster, yet he runs out in the open anyway. Why not stay behind cover?

In taking a more qualitative look at this, these are clearly aggressive cops who have enough experience not to be afraid of running out in front of an armed suspect. They are also part of a particularly violent police force with a long history of police brutality. They know that yelling ‘gun’ will help clear them in court. They trust each other enough; Officer 1 was already drawing his gun before Hinton reemerged behind the dumpster. From the moment he reached for his gun, there was no restraint demonstrated by the officer as the situation evolved second by second. It looks like the officer had already decided to shoot Hinton before he even saw him. Maybe it’s easier for him to shoot first and answer questions later.

Using only still images doesn’t tell the whole story, though. Watching the shooting in real-time shows just how quickly Officer 1 decided to shoot; there was no other thought process. If a gun cannot be seen in Hinton’s hands by examining the video frame by frame, can we trust that the cop saw one in real-time? No, obviously not. He didn’t have to see a gun; he had already made up his mind to kill.

At the very least, that puts the blame on Officer 2 for negligence in giving out potentially false information, which led Officer 1 to shoot Hinton. In any other scenario that didn’t involve a cop, this would comfortably meet the definition of manslaughter.

The argument is not that officers should be expected to make perfectly rational decisions at all times. But, if the result time after time is a police involved killing when they were not threatened, you have a systematic problem. The officer’s automatic decision to shoot to kill is not a single mistake; it’s indicative of an inherently hostile policing culture.

An indictment of the cops involved is a necessity for justice. This situation should not conclude without a proper trial. A crucial detail that must be reconciled is whether evidence was properly handled. Both the gun and the extra magazine were moved from their original resting place at the scene. Any officer who moves evidence for any reason must document the action; failure to do so can be grounds for evidence tampering. There’s a very real possibility that Hinton was shot without a gun in his hands, whether it was concealed in his pocket or left on the pavement. It would’ve been very easy for the officer to move the gun from Hinton’s pocket, supporting their narrative. Alternatively, if it was actually left on the pavement, they could’ve just moved it to his body. The extended footage will hopefully clear this up if they indeed kept recording. It wouldn’t be the first time cops have planted or tampered with evidence.

The problem with completely absolving the officer without a proper trial is treating these incidents as if they were pure accidents, which they’re not. Outside of this case, there’s a system behind it that leads to these outcomes. These cases must go through the court system to create the side effect of accountability. If police cannot hold themselves to a standard where taking the life of a non-threatening suspect is unacceptable, the courts and the community must do so for them.

In many cases like these, all the agency is taken from the person killed. Are there other things Hinton could’ve done to keep himself alive? Maybe. But at a point, there’s only so much someone can do when a cop has already decided to use lethal force. No one expects to be shot and killed in an instant. Hinton wasn’t trying to harm the officers; he was trying to escape a regrettable situation. Even if Ryan Hinton had a gun on his person, does that mean the punishment for running away is death? There won’t be a trial to prove Hinton’s guilt or innocence, the officer already decided his fate. About 3 in 10 Americans own firearms in America; are they allowed to be killed anytime a cop decides, because they are suspected of committing a crime? Giving cops the power to shoot suspects makes that person guilty until proven innocent.

When a system of laws and institutions gives cops a special status above everyone else and absolves them of abuses because of plausible deniability, you get an American police force that kills at 5 to 22 times the rate of other developed nations. Those numbers cannot be produced by ‘bad apples.’

I often think back to the lesser-known case of the ‘Simon-Says Cop’ who shot and killed Daniel Shaver. In January 2016, hotel guests called about a man pointing a rifle (ended up being an airsoft gun) out a window. Police arrived and prepared a raid on Shaver’s room. Shavers had one friend in the room, and they were both drinking. Police yelled for them to exit the room, but they didn’t hear it. Then, police called the room’s phone for them to exit, so they complied. After walking into the hallway, the police were standing away from them with multiple guns trained on them, and gave them a series of complicated commands. In his intoxication, Shavers struggled to follow them as the officer contradicted himself numerous times while yelling with increasing aggression. Shavers pleaded for his life while crying. Finally, the officer commanded him to crawl toward them and then opened fire, killing him. The horrific body camera footage wasn’t released for 1 year and 11 months later. The officer, Philip Brailsford, was acquitted. That is just one example of disgusting injustice on a systematic level that calls every other case into question.

These are murders, not accidents. None of these people will get the justice they deserve until the entire system is dramatically changed, reformed, and abolished for something better.

Rest in power Ryan Hinton. 🕊️

It continues to boggle my mind when I see police shooting fleeing people—especially when multiple officers unload their weapons at once.

As you noted, in modern police culture, deadly force is justified not by any objective threat but by the officer’s perception of danger—“I feared for my life.” Critical theory in the 1990s emphasized that structural harm is invisible except from the standpoint of the harmed, while trauma studies elevated subjective experience—especially of speech, symbols, and microaggressions—as the primary evidence of injury. Since police culture is embedded in the wider culture—everyone’s watching the same revenge porn—why should we be surprised that the officer’s feelings now define the threshold of threat?